7. What Future for the National Curriculum for England

Does a Knowledge Based Curriculum Serve the Interests of the Ruling Class?

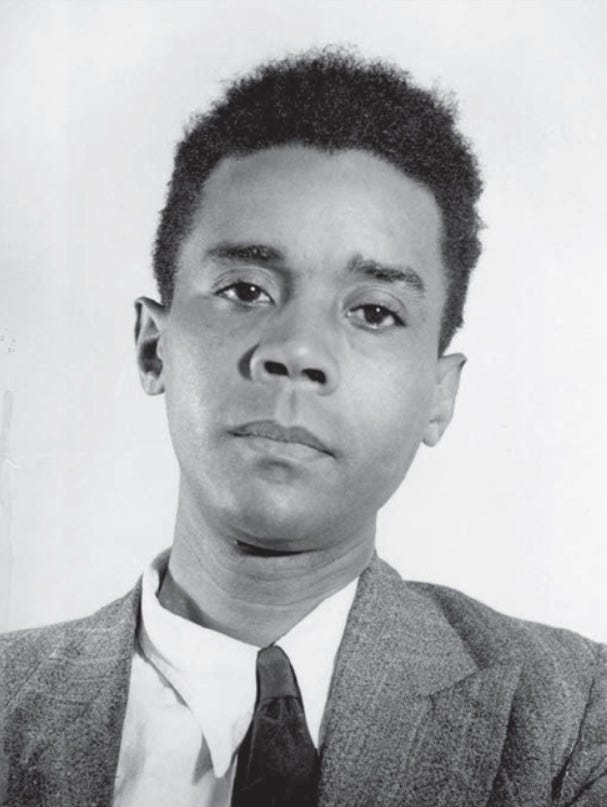

Cyril Lionel Robert James, photographed in 1938

“I denounce European colonialist scholarship. But I respect the learning and the profound discoveries of Western Civilisation. It is by means of the work of great men of Ancient Greece; of Michelet, the French historian; of Hegel, Marx and Lenin; of Du Bois; of the contemporary Europeans and Englishmen like Pares and E.P. Thompson; of an African like the late Chisiza, that my eyes and ears have been opened and I can today see and hear what we were, what we are, and what we can be, in other words - the making of the Caribbean people.”

From a speech delivered by the Trinidadian Marxist in 1966

Since I last posted, quite a few things have happened. One important thing, for me at least, was that I was given the opportunity to present my argument on the history of the National Curriculum to colleagues at the Cambridge Knowledge Symposium. You can read my presentation here. Participation in this event meant that I had to temporarily pause writing this blog series, so apologies for the delay to those who have been following it.

The 2024 Curriculum and Assessment Review

Another, far more important event, for all of us, and for the future of the National Curriculum for England, has been the election of a Labour government in the United Kingdom. This government, faster than I expected, has announced a review of the National Curriculum, whilst also making clear that it will soon become compulsory for all state funded schools to follow it. Previously academy schools could apply for an exemption. With this change the National Curriculum has become more important than it was.

The specifics of the new National Curriculum are yet to emerge, as Labour has only just set out the review’s terms of reference, but there are a few observations that we might initially make.

My first observation is that the review has committed itself to “evolution, not revolution”, which seems sensible to me. It has also made clear that the government is committed to the maintenance of intellectual standards and that it will protect academic knowledge within the curriculum, with a number of important qualifications. You can read the review’s terms of reference here.

In addition to this, Labour has stated that schools should be taking arts education more seriously than they have been, which as a film studies teacher I of course welcome. Studying the arts in the form of literature alone really is not, in my view, sufficient to count as a rounded arts education, although I do also believe that the art of literature is especially important, as literature is constructed through words and we also think and learn through them. So literature, like English more broadly, has a very special and unique place within the school curriculum.

But there are other elements of the review’s terms of reference that invite a more critical initial reply, which I will offer in the belief that this is going to be a genuine consultation, and one in which viewpoints will rightfully differ, and usefully so, even if it’s up to our elected government to make the final decision on how the curriculum should change.

However, I won’t here say all of the things I want to say about the review, as I think these points will be better made after my history of the National Curriculum has been presented. But I would like to raise one issue, which relates to the comments on the National Curriculum made by sociologist Stephen Ball highlighted in the last post.

In my view, Stephen Ball’s way of thinking about the curriculum really does not help us to move forward. Principally my objection to his perspective relates to my belief he does not take knowledge itself seriously, as something that should be valued for its intrinsic and internal powers, and as a useful starting point for the analysing and reforming the National Curriculum.

I will expand on this point later, but here my basic reply to Ball is that he mistakenly views knowledge as an instrument of power, rather than a resource through which power might in fact be criticised. To use a couplet drawn from Michael Young, Ball has a one sided view of knowledge, he sees it as knowledge of the powerful, which the elite use to secure their social position, rather than as powerful knowledge, and as something that helps us all to understand our natural, individual and social worlds, including the position of the powerful. Of course, knowledge can be used for propaganda purposes, and often is, but it is also more than this. This is why I teach.

Ball describes himself as a “policy sociologist”, which means that he studies the formation and impact of state policy, and it is clear that in his study of education policy he draws most significantly on the most cited intellect within contemporary social theory Michel Foucault, as well as ‘radical’ sociology more broadly. Much of what Ball argues mirrors existing Marxist theories of education, particularly in terms of the curriculum, which many contemporary Marxists, and Ball, see as serving the interests of the ruling class, as opposed to the working class pupils that constitute the vast majority of pupils taught in English schools.

But here I’d like to point out that unlike the classical theory of Marx, which continues to offer a range of striking insights into the modern world, Foucault’s work, and that of his followers, evidences a deep, and in my view destructive, ambiguity on the question of truth - it is something created by the powerful - and also holds to a truncated, and negative, conception of human freedom, which is seen as no more than a mechanical reflex of power. These two points, but especially the point on truth, will be developed in a subsequent post, as they are the cornerstone of my critique of Ball’s sociology of the National Curriculum.

This is why I opened this post with my favourite quote from the humanist and Hegelian Marxist and activist for social justice CLR James, a person who nobody could not rightly be accused of being an apologist for the bourgeois social order. James, I think, provides us with an alternative intellectual starting point to Ball’s notion of the ‘curriculum of the dead’, in so far as he sees a great deal of living and current value in the intellectual achievements of those who have died, sometimes thousands of years ago. Following James, I think that one important function of the school curriculum is to preserve and to pass on the powerful knowledge that humanity has accumulated over time.

The point that James is making in the quote, with typical force and great eloquence, I take to be left Hegelian in its intellectual origins, in so far as it sets out a dialectic between knowledge that we acquire and our sense of our own agency in the world. For James, knowledge of oneself, as a historically situated subject, is formed through an engagement with a knowledge of the past, and this desire to know one’s making is no doubt spurred by the desire to remake oneself in the present and to shape the future. This is why there is nothing politically conservative about the conservation and transmission of knowledge within education. In fact, one might go so far as to argue that imagining radical societal change, such as that which James wished and fought for, but failed to realise, in fact depends on an engagement with the knowledge of the past. You cannot imagine the new if you don’t know who you are and what has been and how this has been understood and how these understandings have shaped the world in which you find yourself.

The Tyranny of Relevance

Ball, as we have seen, has a similar concern with the relationship between canonical knowledge and the subject, but in his critique he seems to assume that an engagement with the knowledge of the past is necessarily oppressive of the subject and it is clear that Ball wants students to be liberated from the bondage of tradition. In the quote, Ball argues that old fashioned curriculum content does not speak directly to students’ contemporary experiences, as young women, as young black people, as young members of the working class. He sees all of this as a cultural imposition from above that aims to subordinate us.

As I have previously argued, I share many of Ball’s concerns over the curriculum, but I also think his starting point is deeply mistaken, both in terms of his conclusions and the ways in which he analyses the National Curriculum. I will return to this second more methodological point in a subsequent post, but I’d like to suggest here that a curriculum based on the sentiments expressed by James would be a positive one. It would be a curriculum that was optimistic about the ability of learners to go beyond a narrow preoccupation with immediate experience. It would assume that all students can enter into a dialogue with the great intellectual achievements of humanity, so as to better understand themselves and the world around them.

Our starting point in thinking about the curriculum should be the belief that students really can make a leap into the intellectual past through their imagination. Students don’t need to be taught about themselves directly, although they will learn a great deal about themselves by coming to understand how others struggled to develop self-knowledge. In fact, I’d suggest that our duty as teachers is to engage the young with symbolic worlds that are entirely foreign to their immediate experience, both for the intrinsic value of knowing about the past, and how it has been imagined, but also because in doing so they will come to better know the specificity of their contemporary self. You really don’t have to be a Ceasar, or be looking to assume this role, to learn a lot about life, and the operation of power, through the study of how the Caesars of the past have once governed. So more broadly it is my view, and the view of James, that there is something of enduring cultural value in the intellectual traditions and cultural representations of the past.

Western Culture

James’ quote raises another important issue of relevance to current debates about the curriculum, and in particular the notion that there exists something which is called a “colonial curriculum”. I think many of those who advance this idea have a one-sided view of knowledge that is similar to that of Ball. I don’t know what James would say about the idea that the curriculum of Western educational institutions are colonial, and I suppose that I should not speak for him, but given his quote, I would imagine that if James were with us today, he would take issue with the decolonisers.

In the quote above I take it that James is pointedly defending Western culture, but not uncritically. The way in which he approaches Western culture is similar to my orientation towards the liberal curriculum, I think. Western culture is not something that should be defended exclusively, uncritically or dogmatically. And for the Marxist James this culture, and its traditions, includes, as we might expect, the liberation theory of Marx, and his followers from his time, who for all their many well documented faults, have sought to draw attention to the tension points within a culture that at its finer moments has had the audacity to represent and speak for all of humanity, whilst also, of course, denying that humanity to many.

Further, James reminds us that those of us who are fortunate to live in the West really ought to remain open to the contribution of others who happen to find themselves living geographically elsewhere. Humanity has never lived in total isolation from itself, at least in the modern era, and the culture that emerged within the West is a reflection of that fact.

Further, James reminds us that those of us who are fortunate enough to live in the West really ought to remain open to the contribution of others who happen to find themselves living geographically elsewhere. Humanity has never lived in total isolation from itself, at least in the modern era, and the culture that emerged within the West is a reflection of that fact.

Indeed, we might go further, and draw more directly on Hegel himself, who argues that the spirit of human freedom, which he takes to be the animating force of human history, and to be reflected in the better elements of Western culture, is itself restless, and does not tie itself to any one particular location for too long. For Hegel Napoleon Bonaparte was, at one point in history, the embodiment of human emancipation, and was for this reason a world historic, or “history on a horseback”, but that was for that moment and for that one moment alone.

All of this is important for our discussion of the National Curriculum as this curriculum really ought to systematically introduce the young to the intellectual and cultural achievements of the past. There is a powerful legacy there, and the young are entitled to it, and it is the job of teachers and the function of the curriculum to provide them with access to ideas that have shaped the world in which they find themselves so that they can themselves reshape that world in their own image when they come of age. There is much that we have a duty to pass on.

So given that the review has now been announced, I think it important to state the value of past culture and tradition, in response to Ball, but also in reply to the terms that Labour has set out for the curriculum review.

In her letter to the review body, the Labour Secretary of State for Education makes the point that the review ought to develop a new curriculum that is “inclusive, reflecting the issues and diversities of our society and ensuring that all young people are represented.” My fear here, which I hope is unfounded, is that the principle of curriculum relevance might be overstated by Labour, or narrowly expressed, and might be interpreted by the review, and what follows, to mean that our National Curriculum ought to represent in some immediate sense what the young are interested in. That would be wrong, in my view.

My belief is that self knowledge, knowledge of your own making, and of how you might remake yourself, requires serious scholarship, and some engagement with those who might happen to be dead, but who have left us the fruits of their great struggles to understand both themselves and their own making. And it is the great and noble duty of the teacher, and particularly the teacher of the arts and the humanities, to show how irrespective of one’s immediate experiences, artists such as Shakespeare, to take just one example, really do sing songs that have stood the test of time. Could there be a play of greater relevance to many of our concerns today than The Taming of the Shrew?

It is of course true that appreciating songs such as Shakespeare’s requires an effort that is more significant, sustained and imaginative than that which is demanded by today’s more popular troubadours, but we employ and train teachers to encourage the young to make the effort that is required and to themselves embody and model the identity of an educated person.

A traditional knowledge based curriculum does not, in my view, serve the interests of the ruling class. In fact, it might be more true to argue that the ruling class in fact has a vested interest in denying popular access to it.

Jump back:

6. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

Read on:

8. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

Interesting thanks.

I'd trust you with the education of children infinitely more than any political party.

That said, we must deal with the educational and political systems as they are, which IMHO are corrupt and broken beyond repair.

Therefore 'home-schooling' is my answer to children's education.

Gabor Mate (Myth Of Normal) explains much better than I can, as does the Wise Wound by Shuttle and Redgrove; both of which explain generational trauma, and the subjugation of women by men, among many other issues of education, health and governance.