6. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

The Strange Death of the English School Curriculum

“I finished by quoting Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure.

Our doubts are traitors,

And make us lose the good we oft might win,

By fearing to attempt.”

Margaret Thatcher recalls how she ended a letter to a leading industrialist who urged caution as she planned her devastating and ultimately successful attack on the English trade union movement in the early 80s.

From The Downing Street Years, published in 1983, p106.

“ … knowledge in the traditional schoolroom is realised via the traditional curriculum. The preservation and transmission of the 'best of all that has been said and written'; itself a pastiche, an edited, stereotypical, unreal, schoolbook past. A curriculum which eschews relevance and the present, concentrating on 'the heritage' and 'the canon', based on 'temporal disengagement'. A curriculum suspicious of the popular and the immediate, made up of echoes of past voices, the voices of a cultural and political elite. A curriculum which ignores the pasts of women and the working class and the colonised - the curriculum of the dead.”

British policy sociologist Stephen Ball comments on Conservative curriculum policy in Education, Majorism and 'the Curriculum of the Dead', 1993, p210

In this blog series I have so far argued that education belongs to everyone and that we all have a right to express our point of view on its future during this General Election.

At the same time, I have also suggested that in discussing the future of education, and especially the National Curriculum for England, it is important that our discussions are serious, respectful and meaningful. We ought to show respect towards each other as fellow citizens and we should also respect the gravity of the object of our discussion.

The National Curriculum, I have argued, is socially and educationally important, as a statement of the cultural and educational entitlement of all future English citizens. It is also one of the key instruments by which those who govern the state seek to direct the pedagogic activities of the overwhelming majority of teachers in England. Although here, as we previously noted, it is important to recognise that the significance of this particular lever of state power has declined considerably since it was first introduced in 1988.

Further, I have proposed that in order to have the kind of discussion that we need to have during this General Election and after it is important that some facts are brought to the table. As a focus I have suggested that we concentrate in particular on the curriculum’s programmes of study as these deal most directly with the knowledge content of schooling.

Finally, I have argued that any curriculum facts that we gather are unlikely to simply speak for themselves and that we must apply some theory if we are to get to the deeper meaning of these facts.

All of this begs the question: which theory?

Curriculum Theory

There are many different ways in which the NCfE has been studied. And at the time of writing Google Scholar lists more than four and half thousand academic papers and books that have attempted to explain the NCfE and these have employed a great plurality of theories. The disciplines that have most commonly been used to study the NCfE are philosophy, politics and history, as well sociology and psychology.

The approach that his study will adopt will mostly be sociological as I believe that the NCfE is best understood as a social institution that has evolved historically, and which functions in ways that are different to other symbolic institutions. As I see it, the curriculum is an instrument by which society, or at least one section of society, has given expression to its educational ideals and has expressed these through knowledge. To understand this curriculum, I think it is vitally important to locate it with its societal context and to also appreciate that it also operates as a social context in its own right. Psychology and philosophy, as I understand these disciplines, do not really help us to address the social and historical dimensions of the curriculum, although philosophers of education do help us think about many aspects of the curriculum, most particularly its aims, as we have already seen with our discussion of Hirst and Peters.

The Sociology of the National Curriculum for England

Arguably the best known and most comprehensive sociological study of the NCfE is offered by Stephen Ball. Ball describes himself as a policy sociologist, and his particular focus is on capital ‘P’ politics.

In particular, Ball studies the formation of state education and curriculum policy, as well responses to its implementation. He has written extensively on this for more than thirty years and is perhaps best known for his in parts excellent Politics and Policy-making in Education: Explorations in Policy Sociology (Ball, 1990).

In some respects Ball adopts a sociological approach that is similar to that which will be employed in this study, but there are crucial differences, which will be explored more fully in the next post, but the second quote that opened this section provides us with a reasonable sense of Ball’s overall stance on the National Curriculum for England. Ball sees it as a curriculum of the dead and believes that it is deadening for students. And for me his quote illustrates both the strengths and the significant limitations of his argument and approach.

But before we look into the details, I should say that in spite of my disagreements with Ball I do share many of his concerns. Ball worries that the curriculum we have is motivated by a politically conservative impulse which seeks to use schools as a mechanism of social control. I am also concerned that state education might be used in this way, as was the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill and the liberal left philosopher Bertrand Russell (you can read my summary of Russell’s stance here).

Here is John Stuart Mill in On Liberty (1859) on the dangers of state education:

"A general State education is a mere contrivance for moulding people to be exactly like one another: and as the mould in which it casts them is that which pleases the predominant power in the government, whether this be a monarch, a priesthood, an aristocracy, or the majority of the existing generation; in proportion as it is efficient and successful, it establishes a despotism over the mind, leading by natural tendency to one over the body."

(Mill, 2001, p97)

Ball seems to make some similar points with his idea of the curriculum of the dead, but here we should also note that Mill also argued that public ignorance within a democracy was a social evil and he argued that a liberal state ought to take steps to challenge it. Mill proposed, for example, that the state should support those who could not afford to pay for their child's education and that it should take responsibility for running and regulating a system of public examinations, provided they did not indoctrinate. Here is Mill on this issue:

" ... examinations on religion, politics, or other disputed topics, should not turn on the truth or falsehood of opinions, but on the matter of fact that such and such an opinion is held, on such grounds, by such authors, or schools, or churches."

(ibid, p98)

Mill then concludes:

"All attempts by the State to bias the conclusions of its citizens on disputed subjects are evil; but it may very properly offer to ascertain and certify that a person possesses the knowledge requisite to make his conclusions, on any given subject, worth attending to. A student of philosophy would be the better for being able to stand an examination both in Locke and in Kant, whichever of the two he takes up with, or even if with neither: and there is no reasonable objection to examining an atheist in the evidences of Christianity, provided he is not required to profess a belief in them."

(ibid, p99)

So like Mill and Ball I share a concern that the curriculum might have a deadening impact on the minds of the young and I want young people to experience a curriculum that is living, dynamic, open and intellectually stimulating. The thought that our school curriculum might be directed by the dead hands of received opinion and unquestioned authority fills me with dread and horror. Teachers should never forget that they are educating the young to become free thinking democratic citizens. We are not there to fit students into the existing social order, our job is to give them the tools they need to think critically about it.

Whatever we think of Margaret Thatcher it is commonly accepted that she was a politician of rare intelligence and remarkable personal drive. She was also the first female political leader of this country and she came from a humble background. Thatcher’s Oxbridge education opened up success for her on a world stage. She is an English educational success story and a tribute to our system.

In the quote that opened this post, Thatcher draws on the lyricism of one very dead bard and uses this to express with force her view on the present and the future. We might say that she uses the curriculum of the dead to shape the world of living. I want some of that for every future citizen of England. We need to encourage them to value the intellectual resources of the past so that they might then shape the future. This is, I think, a serious point of disagreement between myself and Stephen Ball.

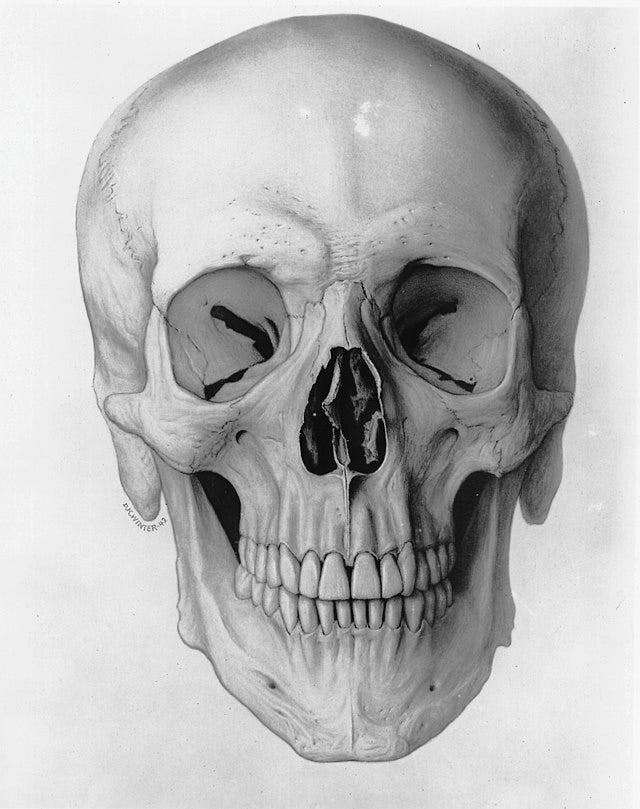

The image is medical illustration drawn by Duncan K Winter and is taken from Wikicommons.

Jump back:

5. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

Read on: