5. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

The Curriculum as an Object in its Own Right

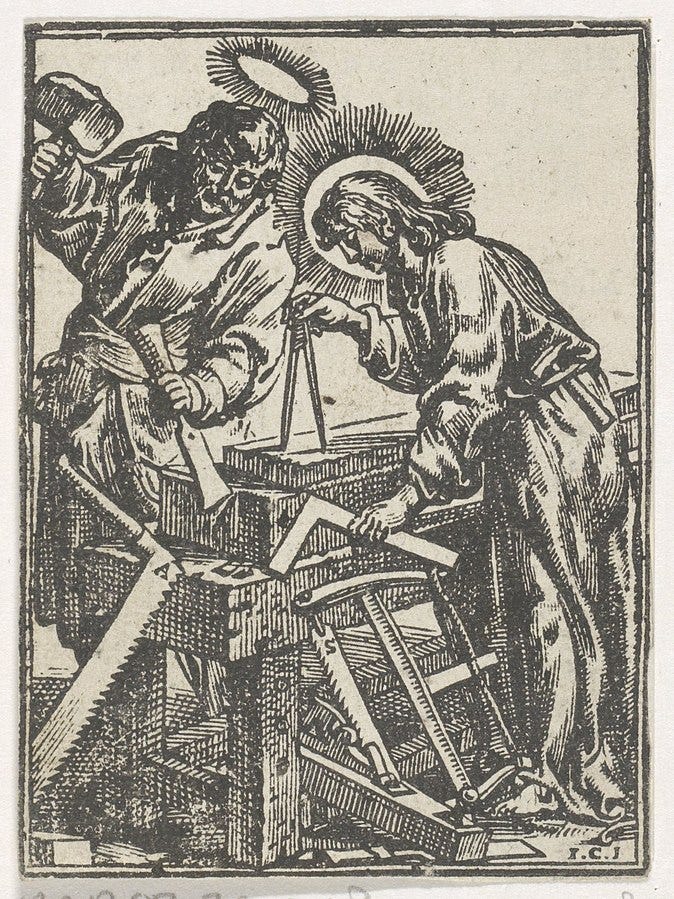

Christ helps Joseph in Carpentry by Cornelis Woons, 1649

Image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum and taken from Wikicommons

“ … most studies have studied only what is carried or relayed, they do not study the constitution of the relay itself.”

Basil Bernstein in Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique, p25, published in 2000

My intention with this blog series is to show how the form of the NCfE has changed over time. In particular, I aim to identify, explain and evaluate the various ways in which the NCfE of 1988 first organised knowledge for educational purposes and subsequent versions then structured knowledge differently.

For this reason my focus will be on those sections of the curriculum that specify what should be taught, or the programmes of study that were previously mentioned by Kenneth Baker.

Within this I plan to use the subject of English as my main case study, on the basis that of all the school subjects it is of the greatest significance, both as a core subject in its own right, alongside maths and science, but also as the language through which all other subjects are delivered.

However, I will also comment in a more limited way on the other core subjects, as well as the wider subject set, so that I might make clear how the common subject structure of the NCfE has developed over time. And I do all of this so that we might have an objective discussion about the future of the school curriculum.

The questions that this blog series hopes to address might be expressed as follows:

How has the subject structure of the NCfE changed over time?

Why?

What is the educational significance of these changes?

My Position on the National Curriculum

Here I should state that the main thrust of this blog series is not to argue for the inclusion or exclusion of any particular content at the level of individual subjects, including English, or even for the relative place of any particular subject within the school curriculum.

However, it might at this point be clear that I do have perspective on both the content and form of the curriculum, as well as the wider question of what the aims of our National Curriculum should be. For the purposes of clarity, I will now briefly explain where I stand on these matters.

My view is that state schooling and its curriculum should principally focus its efforts on the development of the intellectual autonomy of the next generation by introducing them to the fundamental forms of academic reasoning on which intellectual autonomy is based. When we think seriously, we do so through epistemic norms of the disciplines.

Here my thinking has been influenced by a variety of liberal philosophers of education, but especially Richard Stanley Peters and you can read my views on his work in this post.

In what follows below, Peters’ discusses what a liberal conception of education has meant, both classically, but also in the modern era, and what he highlights is that in the modern era our conception of liberal education became more inclusive of practical activities that were valued in their own right, and seen as expressions of our human freedom, in part as a response the mechanisation of labour during industrialisation.

Peters, like many other liberal traditionalist philosophers of education places great value on the development of reason, as an condition of and expression of our freedom, and on the importance of introducing students to the bodies of formal knowledge they need to develop this reason. But unlike some, he sees practical activities, and especially the arts, as also important to realisation of liberal educational aims.

Overall, the point I take from all of this is that in discussing what we mean by liberal education we should always remain open to the various ways in which might cultivate the intellectual freedom of the young, whilst also retaining within our conception of education a sense that those worthwhile activities we engage them in should always involve a form of understanding.

Here is Peters discussing the evolution of the ideal of liberal education:

“The Greek ideal persisted of man who was freed from coarsening contact with the materials of the earth and who developed knowledge for its own sake and in order to control himself and other men. Once, however, especially through the influence of the romantic protest, the practical became dissociated from the instrumental, it became possible to accord intrinsic value to a range of disinterested pursuits in addition to the pursuit of knowledge. Thus our concept of an educated person is someone who is capable of delighting in a variety of pursuits and projects for their own sake and whose pursuit of them and general conduct of his life are transformed by some degree of all-round understanding and sensitivity.”

(Peters, 1972. p9)

But my thinking also owes a significant sociological debt to the work of the currently active English sociologist of education, Michael Young, who is, in my view, the most important theorist of education operating within this country. What Young uniquely adds to the case for a liberal and principally intellectual form of education is some sociological depth, a component of the argument that has typically been missed by philosophers. You can read my review of one of his recent books here. Below Young makes the case for an intellectualist conception of education, one which works squarely within the tradition of the Enlightenment:

“From their earliest days, and increasingly in modern societies, schools have been established as specialised institutions, which can realise some aims and not others.”

As such, he argues, schools contrast with other socialising institutions, such as families. He continues:

“What distinguishes schools is that their primary concern, as embodied in the specialist professional staff that they recruit, and in their curriculum, is (or should be) to provide all their students with access to knowledge.”

(Young, 2014, p2)

Before we move on, I would like to add one further point to my normative position on education and the curriculum, and this relates in particular to the subjects that ought to be included within the compulsory school curriculum. Here my thinking follows that of the philosopher of education Paul Hirst, who proposes that subject selection at the level of the curriculum ought to broadly reflect the wider disciplinary structure of human knowledge. Hirst himself divides knowledge’s structure into seven parts, and there is an extensive and important debate about his division of the disciplines, and some even argue that any overly hard division of knowledge into disciplines perhaps overstates things, as reason is one and the divisions of the disciplines is merely human reason expressing itself in relation to differing objects.

I’ll leave the resolution of this important debate to the philosophers, but here is a quote from Hirst that expresses my position on the curriculum more clearly than I could:

“A liberal education approached directly in terms of the disciplines will thus be composed of the study of at least paradigm examples of all the various forms of knowledge. This study will be sufficiently detailed and sustained to give genuine insight so that pupil’s come to think in these terms, using the concepts, logic and criteria accurately in the different domains. It will include generalisation of the particular examples used so as to show the range of understanding in the various forms. It will also include some indication of the relations between the forms where these overlap and their significance in the major fields of knowledge, particularly the practical fields, that have been developed.”

(Hirst, p133-4, 1968)

The Constitution of the Relay

Overall then this blog series might be understood as seeking to address what Basil Bernstein suggested in the quote that opened this post. In this quote Bernstein argues that what was generally absent from much of the educational research of his day was the study of the ways in which educational contexts and institutions, such as the NCfE, have internal principles and structures which are to some extent distinct from the manifest content.

Bernstein’s point is that when we teach something we invariably transform it into something else. Perhaps his clearest illustration of this point is as follows. In the world, Bernstein argues, we have carpentry, which is a craft, but in a school we have woodwork, which is a school subject, or was when I was a nipper. The two things - carpentry and woodwork - are related, he argues, but they are not identical, as in carpentry a craftsperson does a paid job, and sometimes more, but in woodwork pupils are taught a subject which relates to carpentry. However, in the act of teaching carpentry what is taught becomes the distinctly pedagogy activity and subject that we call woodwork (Bernstein, 2000, p33)

So this study, to put things in Bernsteinian terms, aims to draw our attention to the ‘constitution of the relay’ and the particular relay that is our focus is the National Curriculum for England. Here my wish is to make clear the ways in which this relay, or curriculum, has organised knowledge for pedagogic purposes. In doing so, I hope to introduce an objective element into our discussion of the future of the curriculum.

In the next two posts we will explore how sociologists have understood the curriculum and in the subsequent sections I hope to demonstrate why sociology more broadly is an especially fruitful discipline for the analysis of the school curriculum.

Jump back:

4. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

Read on: