4. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

Having a Meaningful Debate about the Curriculum

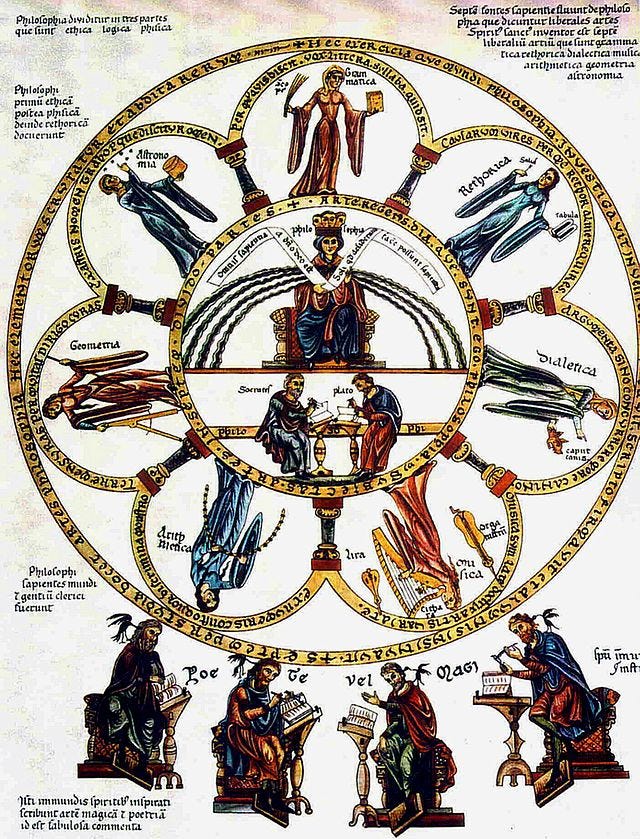

Philosophy and the Seven Liberal Arts illustrated by Herrad of Landsberg for her encyclopedia Hortus Deliciarum (The Garden of Delights), which was completed in 1185. This image depicts the curriculum of her abbey, which beyond philosophy included the subjects of: grammar, rhetoric, dialectic (the trivium), as well as music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy (the quadrivium).

“Most Ministers around the table could not distinguish between the curriculum, covering the full range of knowledge that a child has to absorb, and the syllabus, covering the detailed programme of study leading to an exam. Their views were drawn mainly from their own experience of education or occasionally based on that of their children.”

Secretary of State Kenneth Baker recollects a ministerial discussion of his National Curriculum proposals, from his autobiography The Turbulent Years: My Life in Politics, 1993, p189

Towards the end of my last post I suggested that everybody had both the right and the capacity to express a useful view on education and the school curriculum. Education, and especially state education, which we all directly fund, was, I argued, the property of all, by which I meant all adult citizens of this country.

Within this, it is of course also true that it is teachers who are the most responsible for what happens in schools and it is teachers that have the greatest experience and expertise within their specialist professional field: pedagogy.

Teachers do many important things in schools, but the most important thing they do, and this is their unique social role, is to engage the next generation in the best ideas that previous generations have formed. And they do this so that society doesn’t have to reinvent the cultural wheel.

But here we might also note, for the purposes of clarity, that the ideas that teachers offer to the young are typically, but not always, generated, developed and maintained in places quite different to schools, and most often by the scholarly communities that exist within our universities.

Yet regardless of the valuable expertise of teachers, and the knowledge of scholars, both of which we really ought to recognise, it remains the case, I believe, that we should all be involved in the discussion of the work of teachers, because teaching involves our children, and the future of our society, and all citizens within our polity should have an equal say on this. At the very least the effective functioning of education depends on the active support of the public and democratic discussion is the way that this support might be secured.

A Serious Discussion of the Curriculum Requires Theory

However, whilst it certainly is important that we all get involved in the discussion of the curriculum, I most certainly do not believe that the opinions of everyone are equally true, or well informed, or well judged.

Indeed, many opinions on the curriculum I hear are simply false, or ill informed, and some that I listen to are just plain cranky.

So with reference to the object of our discussion, what resources might we need to have a good debate over the curriculum?

I think our discussion of the curriculum requires us to marshal and to integrate at least three things: facts, theory and judgement.

It is perhaps self-evidently true that our discussion of the curriculum should be informed by facts, because if we cannot first objectively discuss the features of the existing curriculum, and why it has taken the form that it does, then we will not be able to even begin talking about how it might be changed and improved. It is my hope that this blog series will make clear some important facts about the National Curriculum, or will, at a minimum, make evident what type of facts we need to gather.

It is also true that to fully understand the facts that will form the foundation of our discussion we will need to apply some theory, as getting the meaning out of important social facts such as those with which we are concerned requires an analysis that uses theory. As Kenneth Baker rightly observed above, far too much discussion of education relies rather too heavily on subjective personal experience. Theory helps us to get beyond this and to generate more truthful insights into education, as do systematically gathered facts. And when we combine the two, we get to a higher level and more serious discussion. In these higher level discussions theory asks questions of the facts, just as facts ask questions of the theory.

Finally, I think that any serious discussion of the curriculum must also address values, as well as experience and judgement. With regards to this, teachers certainly do not have any kind of monopoly on the values that should be central to education, as this discussion is far bigger than them, but what teachers do bring to the table is experience and often good judgement. Teachers, like any other category of professional, often get things wrong at work, and they often exceed their professional warrant (which you can read about here), but they do uniquely have an insiders’ feel for how things work and might work better in terms of pedagogy. This is why it is important that teachers are listened to in the wider political discussion of the curriculum and state education. And dismissing teachers collectively as The Blob, as Gove once did, really is not very helpful (you can listen to my views on Gove’s entirely unsuccessful teacher ‘negotiating’ tactic here).

So a significant section of this blog series will be taken up with the facts of the curriculum, and I hope to be as accurate as I can be in my description of the facts I have gathered, but I won’t go into these now.

Similarly, the concluding parts of this series will address issues related to values, experience and judgement, especially when I consider what I believe should happen next with the National Curriculum for England.

So the final ingredient that is missing for a good debate on the curriculum is theory, which will be the focus of the next few posts. These will address how we might go about studying the National Curriculum for England in order to consider how it might be improved.

Jump back:

3. What Future for the National Curriculum for England?

Read on: